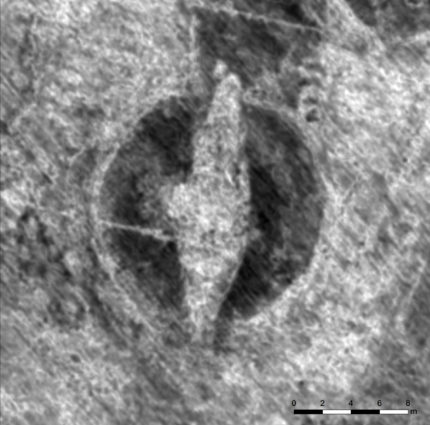

The couple were pulling up the floor to install insulation. Photo: Nordland County Council

A couple in northern Norway were pulling up the floor of their house to install insulation when they found a glass bead, and then a Viking axe. Now archeologists suspect they live above an ancient Viking grave

"It wasn't until later that we realised what it could be," Mariann Kristiansen from Seivåg near Bodø told Norway's state broadcaster NRK of the find. "We first thought it was the wheel of a toy car."

Archaeologist Martinus Hauglid from Nordland county government visited the couple last Monday and judged taht find was most likely a grave from the Iron Age or Viking Age.

"It was found under stones that probably represent a cairn. We found an axe dated from between 950AD and 1050AD and a bead of dark blue glass, also of the late Viking period," he told The Local.

Read the rest of this article...